Philly Sour from Lallemand is a relatively new yeast strain that is rapidly gaining popularity due to the also increasingly popularity of sour beer styles. This particular yeast strain has some interesting characteristics that makes it unique and sets it apart from other yeast strains and methods used for creating sour beers.

History and Discovery

Philly Sour was discovered by an undergraduate student, Stiven Mita working at the University of the Sciences in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania in the lab of the Assistant Professor of Biology and Directory of Brewing Science - Matthew Farber.

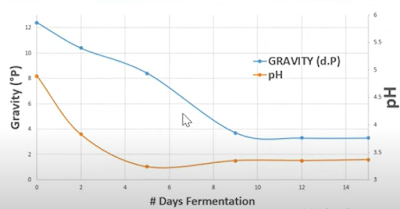

Matthew mentions that the yeast was actually discovered in a graveyard neighboring the University of Sciences grounds in Philadephia. A quick search on Google Maps indicates it was likely the "Center Circle" graveyard or perhaps neighboring "The Woodlands Community Garden" where this particular yeast strain was found. Pretty cool and obviously explains how the yeast got it's name.

Further research suggests that the yeast came from the bark of a dogwood tree located in this parkland/cemetery area.

Philly Sour Yeast Properties

Launched in 2020, Philly Sour is a unique strain of Lachancea species and is a lactic-acid producing yeast. It is unique as it creates lactic acid and ethanol during primary fermentation. This allows the creation of sour beer styles to be somewhat simplified compared to traditional methods of souring.

The lactic acid generated by the yeast helps to lower the pH of the beer, making it more acidic which helps to draw out the natural flavours and characters from fruit making it an excellent choice for fruited sour beers.

Typically sour beers have been created by using multiple yeast strains and/or bateria. Brettanomyces (aka Brett) is a common yeast variety used for souring, and Lactobacillus and Pediococcus are common bateria's also used for the purpose of souring a beer.

Lactic Acid Management

The level of lactic acid obtained is controlled by the amount of glucose that is present in the wort during fermentation. This can be controlled in several ways such as adjusting mash temperature (a higher mash temperature will result in less glucose and less lactic acid), the use of glucose based adjuncts such as dextrose, and adjusting the amount of specialty/highly modified base malts. The use of more specialty malts will result in less lactic acid production, and the use of more highly modified base malts will increase lactic acid production.

Flavour & Aroma

|

| Image Copyright of Lallemand Inc |

Aroma and flavour is described as sour, with notes of red apple and stone fruit, most notable peach. Red apple flavours are very prevalent early on, but these tend to fade and mellow into stonefruit flavours.

Fermentation Properties

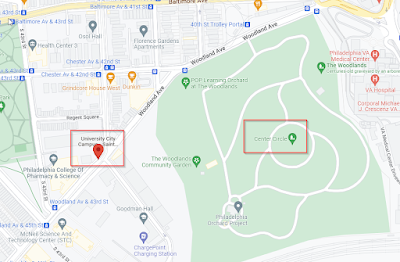

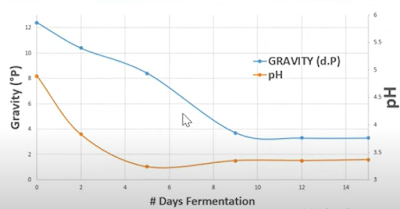

During the fermentation process, Philly Sour initially creates lactic acid during the first 4-5 days, followed by ethanol production towards the tail end of fermentation. "Terminal acidity" is reached around days 2-4, with terminal gravity typically being reached in around 10-12 days. For this reason, it does ferment a little slower than other ale yeast strains. It is considered a high attenuating and high flocculating yeast.

The below chart gives a good visualisation of how fermentation works - in this particular example, terminal acidity or the lowest level of pH is reached at day 5 of fermentation (orange line), after which point the gravity (blue line) continues to fall as fermentation continues and ethanol is produced.

|

| Image Copyright of Lallemand Inc |

Throughout all testing and trails, the yeast never failed to produce lactic acid on it's first pitch.

Fermentation Temperature

The optimal fermentation temperature for Philly Sour yeast is 22C - 27C (71F - 80F). A popular temperature range used during trials was 22C - 24C.

Allowing the temperature to "free rise" during the fermentation works well, along with pitching warm - as warm as 30C has been tested followed by letting the temperature drop back down to fermentation temperature thereafter.

Even when fermenting above the recommended temperature range, no off flavours have been reported. One trial had a fermentation temperature of 33C with no off flavours or defects being noticed.

Fermenting below the recommended temperature range is not recommended as this can lead to under attenuation. As expected a lower fermenting temperature will also result in a slower/longer total fermentation time.

Fermentation pH

The "potential hydrogen" or pH of a fluid refers to how acidic or basic a water solution is. The generally desired starting pH (ie. before fermentation) for most ales is around 5.2 and 5.6, and when using Philly Sour, the desired starting pH is much the same, with a desirable starting pH of 5.2 - 5.4. This is great news for brewers since they don't need to make any further adjustments/changes to their mash or water profiles when using Philly Sour yeast which greatly simplifies the process.

The expected final pH for most beers is around 3.2-3.5. Lactic acid production can be further increased by adding glucose during the early stages of fermentation. Titratable acidity is typically 3-8g/L.

Attenuation Rate

The expected attenuation rate for Philly Sour yeast is 70-85%.

Pitching Rate

Pitching rate is very important when using Philly Sour yeast. Under pitching or over pitching the yeast can lead to reduced souring during fermentation. The chart below outlines the effects pitching rate had on lactic acid as well as ethanol/alcohol production.

|

| Image Copyright of Lallemand Inc |

As you can see, the sweet spot is around 1.5g/L. Pitching at a rate less than this lead to reduced lactic acid production and reduced ethanol production.

Pitching at a rate higher than 1.5g/L also gave slightly lower lactic acid numbers, but ethanol content remains around the same.

In saying that, under or over pitching won't create a poor beer - it will just mean reduced souring due to the reduced amount of lactic acid created - particularly when under pitching.

If you do pitch at a lower rate, then a higher fermentation temperature is recommended. Similarly, if fermenting at a lower temperature, then a higher pitching rate of Philly Sour yeast is recommended.

Adding Fruit

As previously mentioned, acidic beers complement the use of fruit, meaning that fruited sours are a popular style to create using Philly Sour yeast.

The timing of fruit additions during fermentation is important. Fruit being added in the first 5 days of fermentation will help to drive the increase of lactic acid production, and fruit being added later in fermentation (ie. after day 5 of fermentation) will contribute to alcohol/ethanol production.

|

| Image Copyright of Lallemand Inc |

This of course ties back into what was previously mentioned about lactic acid being produced by the yeast during the first 5 days of fermentation, followed by ethanol/alcohol being produced after day 5.

Some popular fruits that were used during trials are; mango puree, fruit concentrate, aronia berry juice, pineapple and pineapple puree.

Adding fruit during the early to mid stages of fermentation can help to rouse the yeast and drive fermentation along.

Fruit that is added after primary fermentation has completed is not recommended as the yeast is highly flocculant and may not efficient metabolize/consume late sugar additions such as those by introducing fruit this late.

Impact of Lactose

Philly Sour does not ferment lactose, so any lactose present in the wort will remain so after fermentation has completed. This can help to contribute to residual sweetness and may be desirable in certain beer styles. The use of lactose had no other perceivable impact on fermentation character/results so is considered fine/safe to use in recipes fermented with Philly Sour yeast.

Co-Pitching Yeast

Co-pitching another yeast variety at the beginning of fermentation along with Philly Sour is not recommended as Philly Sour tends to be outcompeted - meaning souring/lactic acid production won't occur. After day 4-5 of fermentation when terminal acidity is reached, another type of yeast can be pitched to help complete fermentation and/or introduce other unique flavours and esters by using specialty yeast types such as a saison.

Reduced Oxidation?

A really interesting finding is perhaps the possibility that Philly Sour can help to protect packaged beer against the effects of oxidation. In an experiment run by Glenn Harrison from Ellerslie Hop, a number of beers were bottled with differing amounts of Philly Sour yeast being added to the bottle during packaging. The results are pictured below;

|

| Image Copyright of Lallemand Inc |

As you can see clearly just by looking at the colour of the samples above, the control sample appeared heavily oxidised, with all the other samples with differing levels of Philly Sour yeast being added showing reduced amounts of oxidation. Even with as little as 0.5g/L added, there was a noticeable difference in the end colour of the beer.

It's also worth pointing out that the pH for all these samples also remained unchanged - further demonstrating that lactic acid production only occurs during the first few days of primary fermentation and not after primary fermentation has completed and there is alcohol present in the wort/beer. There also wasn't increased attenuation in the samples as a result of adding the Philly Sour yeast to the bottles.

This is only a single test/experiement but sure provided some interesting results - there's obviously much more to be discovered with this special strain of yeast.

Interestingly though, Lallemand state that bottle conditioning is not recommended since the primary sugar will be converted into both lactic acid, ethanol and CO2 and may give inconsistent results. They recommend using Lalbrew CBC-1 yeast to bottle condition fermentations done with Philly Sour yeast.

Cleaning and Sanitation

Since Philly Sour is a yeast strain and not a type of bacteria, standard brewery cleaning processes and chemicals have proven to be sufficient to control and sanitise equipment like fermenters that have been in contact with the yeast. This is a big benefit of using this particular method for creating sour beers, as cross contamination using other methods is a real concern which no doubt deters many brewers from attempting to create sour beer styles.

Pressure Fermenting

Initial testing and trials of the yeast did not use pressure fermentation, so it is not recommended that pressure fermentation be used - at least in the first 5 days during the lactic acid production phase. You can of course do your own testing on this one to see for yourself.

Repitching or Harvesting

Repitching or harvesting Philly Sour yeast for re-use is generally not recommended. It can potentially be propogated when pitched for the first time to help increase use and cell count, especially in large scale breweries, but at a homebrew level it is definitely not recommended or necessary. Re-using Philly Sour yeast would likely lead to inconsistent results/outcomes, with reduced lactic acid production. The yeast has never failed to produce lactic acid when pitched for the first time so it's recommended as a "single use" yeast variety.

Rehydrate or Direct Pitch

Philly Sour yeast can be rehydrated before use, or directly pitched/sprinkled into the wort. Testing has been done using both methods with positive results. Do whatever you're comfortable/familiar with.

Sample Recipe

University of the Sciences in Philadelphia were kind enough to share their pilot brew recipe that was used during trials and testing of the Philly Sour yeast;

85% Pilsner

10% Flaked Wheat

5% Flaked Oats

Recirculation mash @ 65.5C for 1 hour.

This would make a great base recipe for a low IBU fruited sour, and will likely be the recipe we use for our upcoming attempt at making one.

Suitable Beer Styles

Philly Sour is a good choice for classic sour styles such as saisons, fruited sours, gose, berliner weisse, sour IPA's and American Wilds It's also encouraged for use with experimental styles, such as fermenting juice instead of wort, or performing mixed yeast fermentations (so long as the secondary yeast is pitched after lactic acid production has occurred as covered previously).

Summary/Conclusion

Using Philly Sour really simplifies the process of making sour beers. Typically sour beers have required multiple fermentations, at varying temperatures, with the use or addition of multiple yeast strains and/or bacteria to get the job done. Typically with a classic brewers yeast to perform the fermentation and create the alcohol, and then a secondary bacteria or yeast strain to produce the acidity or sourness.

Having both steps done by a single product, during a single fermentation is a real game changer and makes the creation of sour beers accessible to any homebrewer with basic equipment.

The lack of risk of cross contamination is also a major benefit since brewers no longer need to use dedicated equipment for souring processes due to fear of unwanted souring in future batches by chemically resistant bacteria strains that remain even after rigorous cleaning and sanitation practices.

The ability to ferment at warmer temperatures without any noticeable downsides is another major benefit meaning temperature control is less of a factor and consideration, especially for homebrewers who don't always have the equipment necessary to do this.

We're very much looking forward to trying our hand at a fruited sour beer using Philly Sour very soon, perhaps when the weather where we are starts getting a little warmer!

Source

We found the majority of this information from Lallemand Brewing's YouTube video on Philly Sour

Related Articles

.png)